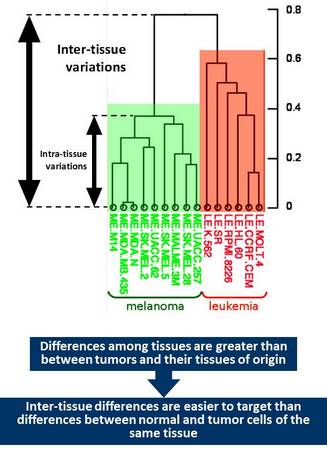

The reality is that differences among cancers originating from the same tissue are far less pronounced than among cancers of different origin. In other words, differences between cancer and its corresponding normal tissue is less pronounced that differences among tissues.

This consideration suggests that if there are factors that are essential for the viability of a particular tissue, tumor cells originating from such tissue would likely retain dependence on such factors. Pharmacological targeting of such factors would likely result in selective tissue toxicity – regardless whether it consists of normal or transformed cells. Such tissue specific targets could be utilized for cancer treatment but only for those tissues that are either not essential for the viability of the whole organism or can be safely replaced. Tissues that belong to these categories include those associated with sexual function (breast, prostate, ovary, and cervix), melanocytes and hematopoietic system. The latter one is obviously essential for our viability but can be fully regenerated using stem cell therapy.

Importantly, there are several notable precedents of successful drugs that act via tissue specific mechanisms and that are actually not anticancer but rather antitissue drugs. They can be divided into three functional categories: (i) targeting signaling pathways essential for viability of cells of certain differentiation (e.g., anti-androgens and androgen receptor targeting molecules used for treatment of prostate cancer), (ii) targeting specific branches of cell metabolism that certain tissues uniquely depend on (e.g., bacterial asparaginase used for treatment acute leukemias since lymphocytes, as well as some leukemic cells, lack the ability of de novo synthesis of asparagine), (iii) directed against cell type-specific surface molecules (e.g., cytotoxic drugs based on CD20 targeting antibodies used for treatment leukemias that retain expression of this differentiation marker).

Therapies that are based on tissue targets are not necessarily equally toxic to normal and transformed cells. Thus, tamoxifen, an estrogen receptor antagonist, caused growth arrest in normal but frequently induces apoptosis in transformed breast epithelial cells.

Anti-tissue drugs are expected to have several advantages vis-à-vis other anticancer agents. For example, they are directed against intrinsic and nearly universal property of cancer cell – its basic epigenetic resemblance of normal cells of certain tissue. The fact that tumor cells almost never lose their “epigenetic destiny” suggests that it would be equally difficult for them to acquire resistance to anti-tissue drugs. High tissue selectivity of this type of drugs to the cells of specific differentiation restricts their general toxicity, which is a common problem for many conventional anticancer drugs. All these ideas stimulated OncoTartis to focus its R&D program on development of anti-tissue drugs.